An innovative method of screening patients for COVID-19 has been created by a research team that looks at the immunological response of the body at the molecular level. Their approach may be able to accurately identify illnesses within a few hours of exposure, which is much earlier than the COVID-19 test can currently do. In the February 27 issue of Cell Reports Methods, the team describes their innovation, which is still in its infancy.

According to study lead author Frank Zhang, who worked on the project as a Flatiron research fellow at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Biology (CCB) in New York, the majority of current COVID-19 tests “rely on the same principle, which is that you have accumulated a detectable amount of viral material, for example, in your nose.”

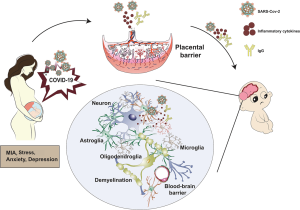

Instead, the new method is based on how our bodies respond when SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, invades them. Certain genes activate when the attack begins. These genes’ segments result in the mRNA molecules that direct the synthesis of proteins. The specific combination of the mRNA molecules alters the kinds of proteins generated, including proteins with roles related to viral defense. The relative quantity of the different mRNA molecules is used in the novel technique to determine with certainty when the body is mounting an immunological response to the COVID-19 virus. The current study is the first to diagnose an infectious disease using such a method.

Blood samples taken before and after the participants in a 2020 study of U.S. Marine recruits helped the researchers fine-tune their procedure. More than 1,000 mRNA-variant ratio alterations linked to disease were discovered by the researchers’ computational methodology.

The new technique produced a remarkable 98.4% accuracy rate when put to the test on actual blood samples. This is especially impressive given that the method is equally effective on asymptomatic individuals, for whom quick antigen testing can only be 60% accurate.The new approach isn’t ready for prime time yet, Zhang says. He and his colleagues only tested blood samples rather than the nasal samples that are more common and convenient for diagnosing COVID-19. Also, they need to make sure they can distinguish between the body’s reaction to COVID-19 and its response to infections caused by other viruses, such as colds.